Real‑world validation still matters for imaging AI

Reading time /

4 min

Research

Over the past few years, intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) detection has become one of the most mature and regulated use cases in clinical imaging AI. Multiple FDA‑cleared models are now clinically used in radiology workflows. However, recent evidence suggests that deployment maturity does not necessarily mean that models are clinically robust.

Since ICH detection has been on the market for a while now, multiple studies on post-deployment evaluation are coming out. Two recent papers examining commercial ICH detection models illustrate both progress and persistent gaps. Together, they emphasize an important lesson for imaging AI research: performance claims are dependent on the data distributions on which models are trained and evaluated. Training an AI model on population A does not mean it will perform well in population B. Understanding where and why models fail is the foundation for the next generation of clinically meaningful AI.

Real‑world performance of a commercial ICH model

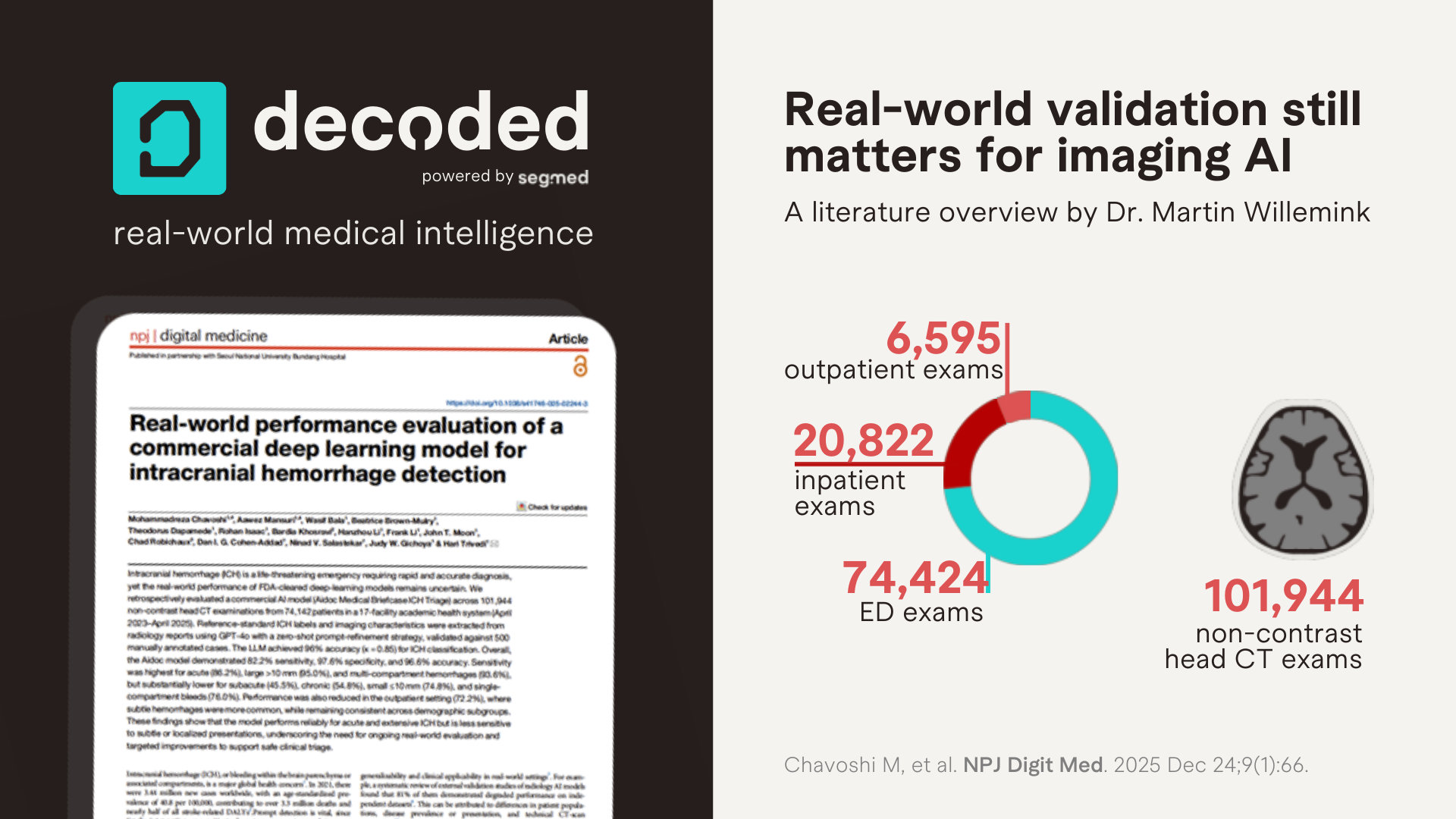

Chavoshi M, et al. Real-world performance evaluation of a commercial deep learning model for intracranial hemorrhage detection. NPJ Digit Med. 2025 Dec 24;9(1):66.

A team out of Emory University led by Dr. Hari Trivedi evaluated how an FDA‑cleared deep learning model for intracranial hemorrhage detection performed across real‑world clinical settings, hemorrhage subtypes, and patient populations.

They evaluated 101,944 non‑contrast head CT exams from 74,142 patients across 17 hospitals in a large academic health system. Reference labels were extracted from radiology reports using a validated LLM‑based framework, with manual adjudication.

Unlike many prior evaluations, this study moves beyond aggregate accuracy and interrogates model behavior across clinically meaningful dimensions: acuity, hemorrhage size, compartment involvement, and care setting. While overall specificity remained high (97.6%), sensitivity dropped substantially for exactly the cases that are hardest for humans: small (<10 mm), single‑compartment, subacute or chronic hemorrhages. Outpatient sensitivity was particularly low (72.2%).

The authors conclude that the model performs reliably for acute and extensive ICH but is less sensitive to subtle or localized presentations. They emphasize that there is a need for ongoing real-world evaluation and targeted improvements to support safe clinical triage.

These findings challenge the assumption that AI triage models uniformly improve detection across all clinical contexts. Instead, they appear to perform best where radiologists already perform well: acute, large, multi‑compartment bleeds.

Although this large-scale study was conducted well, there are a few limitations. Most importantly, this is a single‑system study, potentially resulting in limited diversity of the data (for example technical parameters such as CT vendors, acquisition and reconstruction settings, etc). Second, the reference standard was based on an LLM interpretation of radiology reports, which gives an extra layer of potential false positives and false negatives. It is also important to mention that the authors report systematic performance drops in small hemorrhages, single-compartment bleeds, subacute/chronic presentations, and outpatient settings. These patterns suggest that the commercial model is predominantly trained on acute, ED-centric datasets, high-signal, consensus-positive cases with limited longitudinal variation. However, this cannot be verified since training data details of the commercial model are not publicly disclosed.

Comparison with another real-world validation study

Savage CH, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence Triage of Intracranial Hemorrhage on Noncontrast Head CT Examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2024 Nov;223(5):e2431639.

In late 2024, a group out of the University of Alabama, led by Dr. Andrew Smith, also published an external validation study on an ICH detection model from the same vendor. They also performed a single-center study which was substantially smaller, evaluating a total of 9,954 exams from 7,371 patients. The authors found that the accuracy for ICH detection was slightly better for radiologists without AI (99.5%) compared to radiologists with AI (99.2%, p=0.04). They also found that the mean turnaround time for ICH-positive studies was (not significantly) shorter for radiologists without AI (147.1 min) compared to radiologists with AI (149.9 min, p=0.11). Therefore, the researchers conclude that this real-world study did not support the use of AI assistance for ICH detection.

When viewed alongside Chavoshi et al, we can see a pattern: commercial models often maintain high average performance while masking clinically important failure modes. Without detailed stratification by acuity, size, and care setting, generalizability remains difficult to assess, and difficult to improve.

What does this mean in practice

From a research perspective, these studies underscore a structural limitation in imaging AI development: access to sufficiently diverse, longitudinal, and real‑world datasets.

Models trained primarily on acute care data may never learn to recognize the subtle signal variations that dominate outpatient and follow‑up imaging. Similarly, limited representation across scanner vendors, acquisition protocols, and patient trajectories constrains generalizability.

Real‑world longitudinal imaging datasets that include multiple institutions from different geographic regions and multiple care settings, enable:

• Exposure to low‑signal and borderline cases

• Robust evaluation across clinically relevant subgroups

• Longitudinal modeling of disease evolution rather than binary detection

Importantly, these are not edge cases; they represent the majority of imaging encountered outside tertiary emergency care.

LLM‑assisted labeling at scale

An interesting and exciting methodological solution by Chavoshi and colleagues was to determine the reference standard in a very large-scale study by using large language models to extract structured labels from free-text radiology reports. When paired with expert validation, this approach enables analyses at a much larger scale compared to what was previously feasible. This unlocks the ability to evaluate more subgroups without full manual annotation. As multimodal AI research accelerates, hybrid human‑LLM labeling pipelines are likely to be used more commonly.

Closing insight

ICH detection may be one of imaging AI’s most established applications, but these studies remind us that maturity is contextual. Real‑world performance depends less on model architecture than on the breadth and realism of the data ecosystems supporting it.

These studies show that diversity and heterogeneity of both training and validation data is extremely important for the development of generalizable AI models.